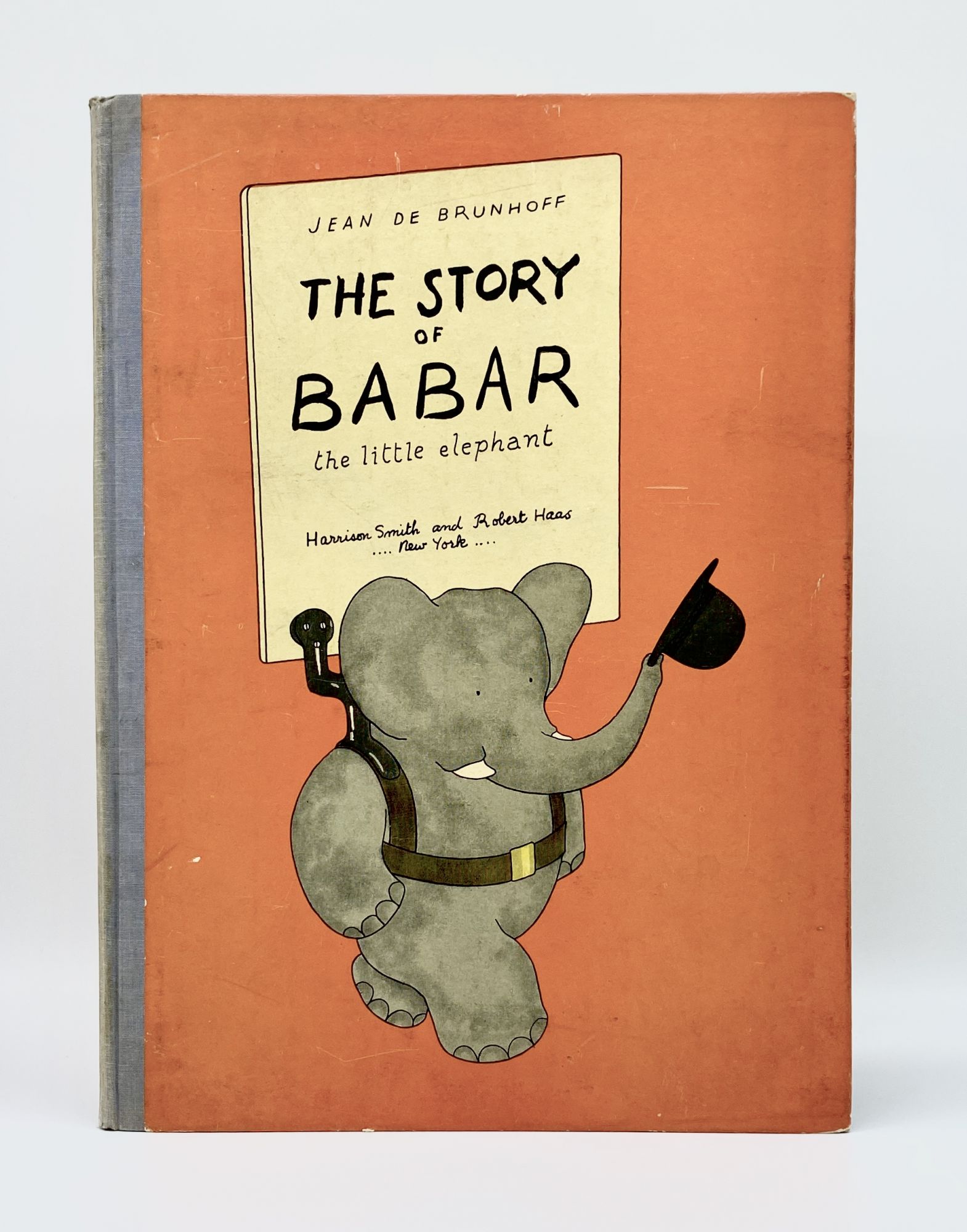

At the end of the bloodless war with the rhinoceroses in the second story, The Travels of Babar (Le voyage de Babar, 1932), the elephant army is jubilant that "La guerre est finie! Ah! Quel bonheur!" ("The war is over! How perfectly splendid!" 46). This bonheur, full of tranquillity, is a fitting culmination to Babar's pluck after his mother's death and his determination fully to embrace life, love, and responsibility.

marriage feast in the The Story of Babar (Histoire de Babar, le petit éléphant, 1931), "Le roi Babar et la reine Céleste, heureux, rêvent à leur bonheur" ("King Babar and Queen Céleste are indeed very happy" 46). Babar's climactic dream is de Brunhoff's personal adaptation of the Psychomachias, the apocalyptic early-Christian allegories of spiritual struggle in the form of a battle between the virtues and vices.īut first, what exactly is bonheur to a non-religious, bourgeois, family-centered French artist born in 1899? And how is it achieved? Outside of the dream sequence Jean de Brunhoff uses bonheur sparingly in fact, in three of his seven books the word appears only once and in three not at all. That doctrine is most fully articulated in the dream sequence in his third book, Babar the King (Le roi Babar, 1933). But though many routes to Babarian happiness have been explored-among them the socio-political, literary, anthropological, architectural, and visual-the ethical and religious implications of Jean de Brunhoff's doctrine of happiness remain unexamined.

Most importantly, the authors' primary message to young readers is still "Vive le bonheur" ("Long live happiness"). In the sixty years since his birth in 1931, King Babar's sturdy character and Utopian milieu have remained essentially as de Brunhoff père developed them before he died in 1937. Babar the elephant-king is entering the seventh decade of his benevolent reign.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)